Thoughts on a Postsecondary Institution Rating System

A presentation at the Postsecondary Institution Rating System Technical Symposium

We need better data. Let me rephrase that. YOU need better data. This should be the Department’s first priority. According to the story in InsideHigherEd in mid-January regarding the deal reached by congressional budget negotiators, the Department is required to submit to Congress a report “on the data it has on Pell enrollment and graduation information by institution.” I suspect that the four months allocated will be ample time to write a report that says, “Not much.” In Virginia, I can turn around a document with retention and graduation rates out to 10 years post-entry for any Title IV or state aid program (or a host of other characteristics) in a matter of minutes. In fact, any user of our website can do so. It can also be broken down by gender and majority/minority student status.

We need a vision for better data and tools that help students and policy-makers make better decisions. This vision involves four primary points:

- Better data, ideally student-level;

- Increased transparency through new metrics and the use of Navigator and the College Scorecard;

- A small number of ratings that are tied explicitly to federal aid programs, such as Pell grants.

- Partnership with states higher education offices.

The Student Right-to-Know Before You Go Act from Senators Wyden and Rubio, with the support of Senator Warner is one model. I hope that the IPEDS Act under consideration in the House results in a study that clearly demonstrates that a unit record collection is the most appropriate and efficient path.

Without significant change to, and expansion of, the IPEDS collection, the Department and Administration should stay out of the business of institutional ratings beyond a very limited scope, which I will describe later. US News & World Report and other publishers have taken existing IPEDS data about as far as it can reasonably go and they collect and use additional data and information that go well beyond IPEDS. College Navigator makes very good use of existing IPEDS data.

If current IPEDS data were adequate for rating and assessing institutions in a complete or meaningful way:

- Most states would not have at least one student-level collection.

- SREB would not have expanded its collections significantly beyond IPEDS.

If we are to envision a rating system that does more to help students and families make better-informed decisions about postsecondary education we need to move away from the simple aggregations of today. We need to provide measures that are relevant to the audience we are trying to reach. We also need to remind them through these measures that effort and work are required to be successful. For example, graduation rates based on full-time and part-time enrollment, paired with time-to-degree, could do a great deal to help students make better decisions.

Virginia has gone through several iterations of accountability in the last two decades. Rarely does a system last undisturbed for a sufficient length of time to determine the effectiveness of accountability systems, or specific measures. We believe in accountability almost as much as we believe we can always make something better. This is perhaps an advantage with a federal system in that the gears grind so slowly here in DC that once started, a system takes awhile to change. The foundational practices at the Department, especially in NCES, to conduct Technical Review Panels (TRPs) and provide public comment periods before adding to, or modifying, collections ensure the involvement of the higher education community. These practices also provide the avenue for some associations to maintain and practice their traditions of obstruction and confusion, especially when it comes to measures that improve transparency.

As much as many people complain about the traditional IPEDS GRS graduation rate, we at least understand it. It has been a stable measure of the community and has developed its own identity. Much of what we talk about today derives from that simple measure of tracking a cohort from start to graduation. This measure is a result of many TRPs and periods of public comment and much research. At one of the meetings of the Committee on Measures of Student Success, Carol Fuller of NAICU, presented the long history of its development. Her presentation reminded me of what I saw dimly from an institution as these discussions took place in DC, as well as the frustrating discussions took place at IPEDS TRP #24 in 2008 as we considered adding graduation rates for Pell students and Part-time students to IPEDS.

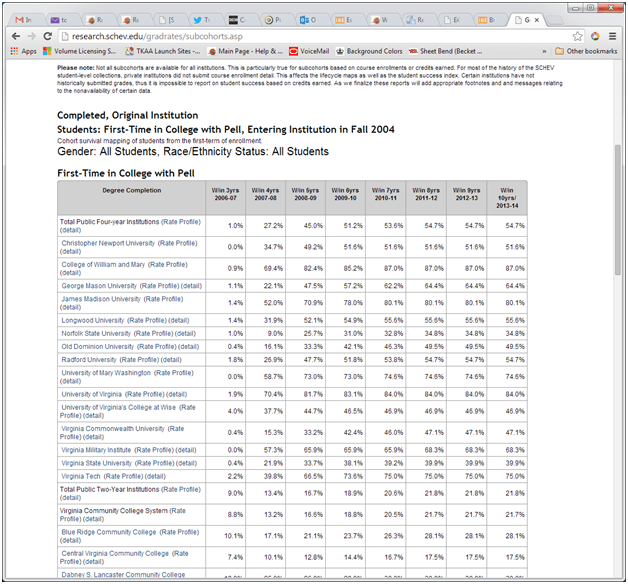

At SCHEV we are moving away from the standard IPEDS measures of the Graduation Rate Survey. We have heard the concerns of the institutions that the first-time, full-time cohort of new students is too narrow. Thus we have created reports based on broader cohorts with multiple sub-cohorts. We follow these cohorts for up to 10 years.

We have an extensive website with a tremendous amount of data available. We have carefully designed reports to keep the focus away from the strict comparison of institutions. This was notably true in our publication of the Post-Completion Wages of Graduates in 2012, and in 2013 the Student Debt reports of recent graduates. Our primary goals are transparency and the establishment of a common base of fact from which honest conversations of effectiveness and quality can be initiated.

We should know what “is” before we discuss what “should be.”

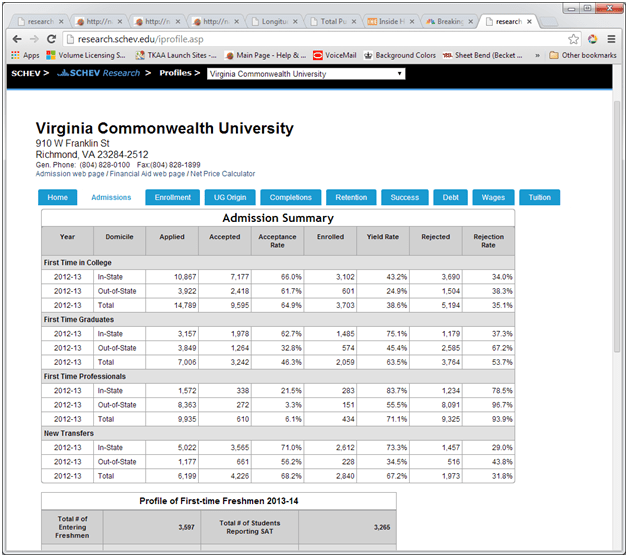

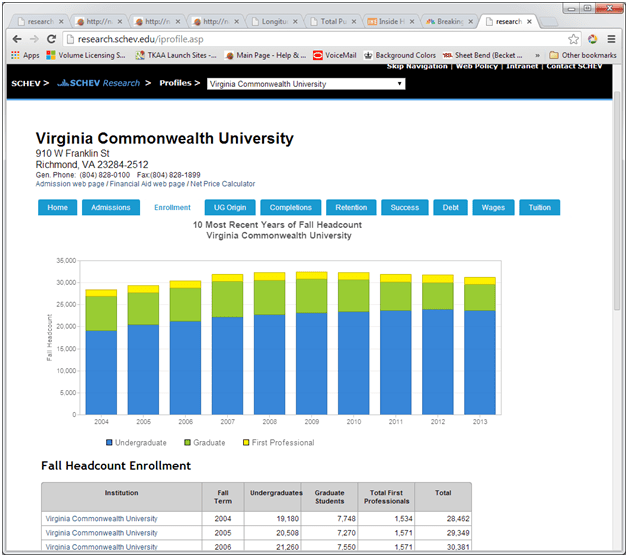

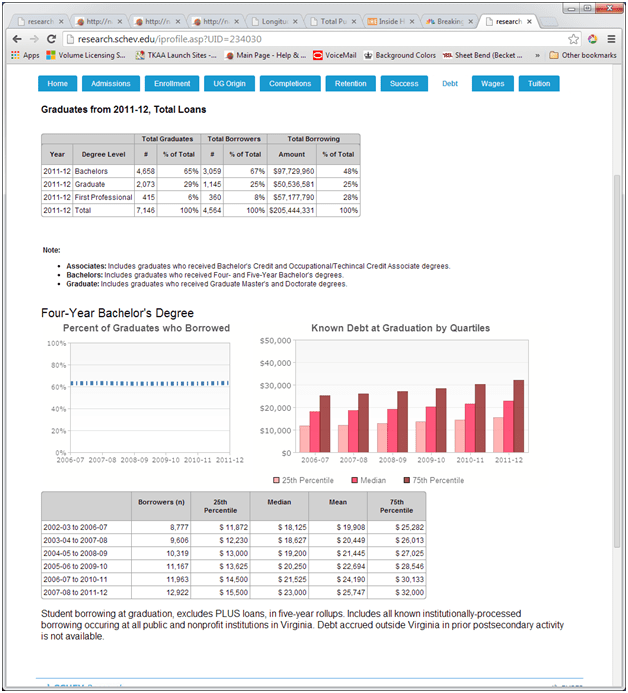

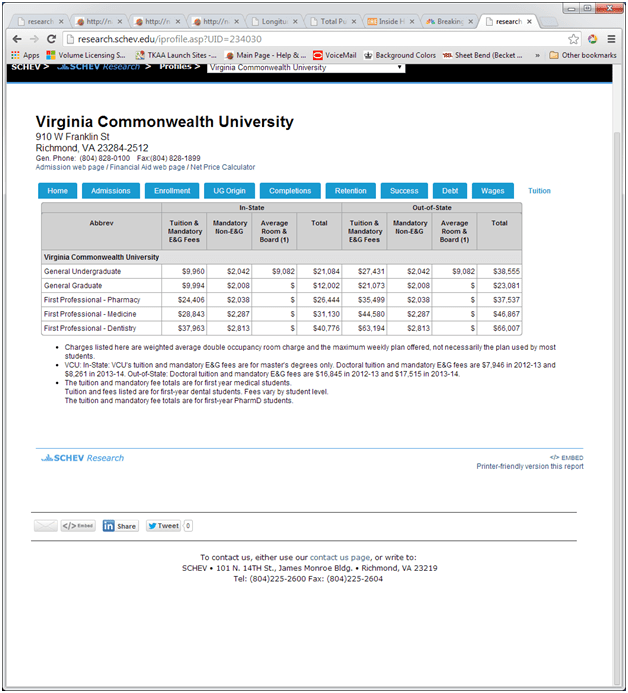

For example, on our institutional profile, we provide the basics: Admissions, Enrollment, Degree Awards, Retention and Graduation, Student Success, Graduate Debt, and Wage Outcomes.

Under Admissions, we provide information on apps, admits, and enrolls for all levels of students, as well as a traditional profile of First-time Freshmen.

In the Enrollment tab we provide 10 years of enrollment by student level.

The UG (Undergraduate) Origin tab maps the number of enrolled undergraduate students from each city/county in the Commonwealth.

The Completions tab provides the recent 10 years of degree awards by level and 20 years of degree awards by STEM/non-STEM categories.

The Retention tab should be of special interest to today’s audience. We have taken cohort graduation rate reporting and analysis to new levels of detail and on this tab provide a small subset of metrics that are available elsewhere on the site. Since these versions follow retention into the eighth year and graduation into the tenth, we include both full-time and part-time students, for fall, spring, and summer starts. These subcohorts include All FTIC (First-Time in College), in-state FTIC, FTIC direct from HS, FTIC with No Financial Aid, FTIC with Pell, and various categories of family income at entry. We also include a graduation rate for students earning at least 60 credits within two years as a reminder to both students and policy-makers that each student must do the requisite work and put forth appropriate effort to graduate. When they do, there is much less differentiation in graduation rates across institutions. After all, a much of the student success equation is in the hands of each individual student – they must do the work to be successful.

Under the Success tab, we introduce the Student Success Index which combines the graduation and persistence rates of FTIC and Transfer, both full and part-time.

The Debt tab builds from recently released reports on student debt of graduates. We provide an overview of borrowing at the institution, and then the debt trends of the dominant undergraduate level degree at the institution. Our debt reports differ from all others in that they include all debt processed (public, private, institutional) through the institution as well as debt of transfer students (including any debt accumulated prior to transfer for in-state students).

Under the Wages tab, we include the summary data on wage outcomes for each level of credential offered by the institution. These data include wage outcomes at 18 months and five years post-completion and what we know of students enrolling in programs post-completion.

Finally, we include a tab on Tuition fees, for all levels of programs at the institution.

These profiles provide a sampling of the data available on our site. They emphasize state policy concerns and objectives without pitting one institution against another. Transparency is provided without the need to attempt defining one institution as better than another. In the absence of clear and believable measures of student learning outcomes, any sense of “better” strikes me as very limited, inappropriate, and misleading, at best. I am further concerned about the possibility that the department might commit to new metrics, with ratings based on those metrics, before anyone has really seen and debated the data. We are better served as a community through the development of measures that are allowed to become stable over time through debate and the development of accepted identity of their value and meaning.

In light of this, I would suggest that desirable metrics be collected and reported out for a period of two years before they are used in a rating system. Only by taking best advantage of the collective thinking of the academic community will we gain their confidence in the ultimate product. It is the urge to rush because of the timeframe of elections that most jeopardizes this project.

Another problem that I think we face with any rating system is clarity in whose behavior we are trying to affect. Clearly, there is a desire here to create a system to direct the distribution of resources. It seems that this will cause institutions to behave in a way to maximize their access to those resources under the guise of remaining, or becoming, more affordable. However, wouldn’t the easiest route to greater affordability be attracting more of those resources? Attracting and obtaining more third-party payments (financial aid) doesn’t solve the problem of rising college costs – it only shelters some students from those increased costs.

If the goal is to use the rating system to affect student behavior, how will that improve affordability? By directing more students to more highly rated institutions? I’m not sure this helps affordability as the economies of scale in higher education only go so far right now, and, more importantly, in my opinion, an institution rating does not necessarily translate to a rating of individual programs. After all, it is at the program level where student engagement really occurs, not at the institution level. I also don’t think government should be picking winners and losers amongst institutions and programs. Requiring transparency is what government can do best.

Even though the Department’s focus is on ensuring access to undergraduate education, institutions are complex entities that do much more than provide undergraduate education. Any rating system created should recognize that reality and provide alternative ratings that are more institutionally holistic. As we know already, the GRS is too narrowly focused to be truly representative of an institution, so let us not fall into the same trap by creating a narrowly-focused rating system. Again, I understand much of the focus is on how to best allocate Pell dollars, but it is not much of a stretch to assume, that should PIRS be successful, it will be applied to the student loan program in some fashion. We should build now for that possibility by considering graduation rate metrics for graduate and professional programs.

In 2008, as a measure of affordability under the Institutional Performance Standards, the Commonwealth adopted a three part measure: graduation rates of students with Pell grants, of students with other aid but not Pell, and students with no financial aid. The intent of the measure is to bring attention to the differences while requiring institutions to work to bring those three measures in line with each other. There really should be no reason why students admitted to an institution, allegedly believed able to do the required work and succeed, should have substantially different graduation rates based on their financial aid status. Besides, no institution is affordable if you have a low likelihood of graduation, if your goal is graduating.

Bob Morse has done comparable work in his blog entries, “Measuring Colleges’ Success Graduating Low-Income,” “Measuring Colleges’ Success Graduating Students with Subsidized Stafford Loans” and “Measuring Colleges’ Success Graduating Higher-Income Students”

The Request for Information is clear: “the President will propose allocating financial aid based upon these college ratings by 2018.”

My questions are these:

• How complex do these ratings really need to be?

• Is this really about the allocation of aid or, more likely, about denying access to aid programs to certain institutions?

Greater complexity perhaps will allow a system that looks at the entirety of an institution and how that affects undergraduate education. Is it really necessary? If the department were to collect or calculate (under a UR collection) a package of graduation rates comparable to what we have done in Virginia, standards could be developed to exclude participation in the Pell grant program if the difference between graduation rates for non-aided students and Pell students was greater than the standard deviation of the national sample for that size and type of institution. Additional incentives could be provided of some kind, perhaps additional Pell dollars, for institutions that demonstrate three consecutive years of growth in graduation rates of Pell students, or, for increased annual student retention. My strong suggestion is to place the most direct measurement possible on the thing you care about.

Beyond direct measures of this type, community colleges should not be rated. They should be transparent, but they should not be rated. The large numbers of place-bound students these colleges serve don’t need ratings. They need academic support and financial aid. They will benefit from increased transparency about wage outcomes, employment market, debt, and transfer outcomes.

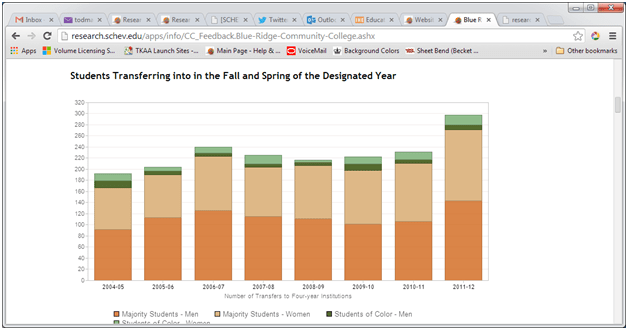

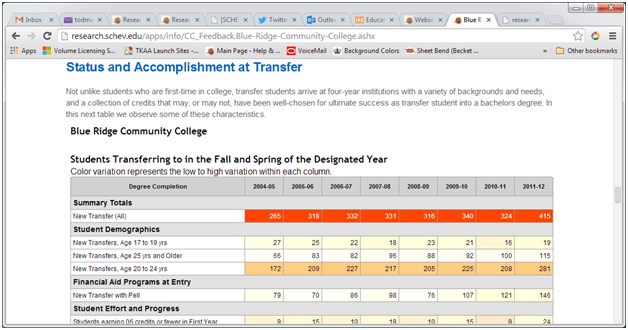

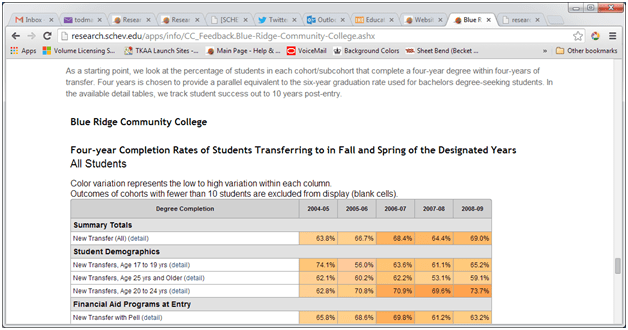

Without luck, nothing ever changes for the good, if we never know that it is bad. Every institution should have available to it the depth of transfer reports that we provide. Whether community college or four-year college, origin or destination, institutions and students need good information about student outcomes. We provide transfer feedback based on our subcohort models following students for up to 10 years.

Finally, the most important thing that the Department can do is to embrace the States as partners in these endeavors. Not only are we responsible for nearly all the public institutions in the nation, we have close relationships, tied to operating approval, to all other institutions.

We also have better data.

Virginia has 20 years of student-level data on public and nonprofit private colleges. It covers enrollment, completion, and financial aid. It can meet, and easily exceed, all the current IPEDS reporting requirements about students. If the Department is permitted to make the move to unit record, it would be most efficient to build a collection model that takes advantage of the state-level collections in place now. There is no reasonable need to require institutions to submit student-level data to both the state and the feds. Plus, I assure you, state collections are not going away. We have greater needs as our data are used for funding models and more. These are needs that cannot be met by the existing burdensome IPEDS aggregate surveys, or by relying on a federal unit record collection. We often have mandates in existing law for certain reports from our data collections. This is certainly true in Virginia.

There are things we can’t do though.

We don’t have access to student loan repayment and default data. Access to repayment data would allow Virginia to enhance its data products and the understanding of the specific impacts of student debt and employment outcomes in the state. Nor do we have access to Social Security Administration earnings data or wage data outside our state the inclusion of which would allow us to provide very accurate and complete data to our constituents. We also do not have access to good data on veterans.

This is where the federal government and the States can work together to establish a partnership that can result in better data for everyone.

This is what the Student Right-to-Know Before You Go Act is designed to address. In full disclosure, I provided significant technical advice on both versions of the bill. I did this because I think it can improve transparency in higher education.

One of the best roles of government is to ensure equal access to meaningful information. Consumer information and transparency are wonderful tools and can lead to a better informed consumer. However, that does not mean behavior necessarily changes.

A number of people have commented to me that federal government requires a variety of safety and performance ratings on new cars and trucks. This is true. It is good information and sometimes the EPA ratings can actually be achieved. However, the most fuel-efficient and safest car is not the largest seller. The Ford F-150 has been a number one seller for some years now. People buy what they want and what they need, not necessarily based solely on measures of safety and fuel efficiency.

Choosing a postsecondary program or college experience is not much different. At best, I think this endeavor will lead to the great majority people making the same decisions with better data. However, if the decisions of some students improve, with matching improvement in achieving their goals, then it will be worthwhile.

I want to conclude with this thought.

In his TEDx talk criticizing TED talks, Benjamin Bratton, a visual art professor at University of California-San Diego says the following:

“Problems are not ‘puzzles’ to be solved. That metaphor implies that all the necessary pieces are already on the table, they just need to be rearranged and reprogrammed. It’s not true … If we really want transformation, we have to slog through the hard stuff … we need to raise the level of general understanding to the level of complexity of the systems in which we are embedded and which are embedded in us.”

I think this is true. Higher education is an exceedingly complex enterprise and no rating system is going to change that or make it appear less complex to those new to the process. And this is okay. Bratton’s comment about problems apply equally to the college search process and raising the level of general understanding about what postsecondary education means to an individual and the nation. Providing greater transparency and increasing the number of players in the information market will do more to achieve this goal than an attempting to build a one-stop mega-mart of higher education data and institution ratings. Students and families should expect, and be expected, to put forth some work and effort to decide the best path of postsecondary education for each student.

The time allocated today is far too brief for a technical discussion about the specifics of what can and should be done. I will be glad to work with the Department throughout the development and implementation of these ratings and a revised data collection. The Department should focus on:

- Better data, ideally student-level;

- Increased transparency through new metrics and the use of Navigator and the College Scorecard;

- A small number of ratings that are tied explicitly to federal aid programs, such as Pell grants.

- Partnership with states’ higher education offices.

Pingback: Duncan doesn’t understand the opposition to PIRS | random data from a tumored head

Pingback: The new phone books are in!! | random data from a tumored head

Pingback: Where are the Dancing Horses? | random data from a tumored head

Pingback: Two Ratings – Why Not Five? | random data from a tumored head

Pingback: The GERS grind slowly, but they grind | random data from a tumored head